|

|

While Vietnam's human capital index is high, ethnic minorities need more inclusive policies

|

Daniel Dulitzky, East Asia and Pacific regional director for Human Development, World Bank said at the National Conference on Sustainable Development 2019 that, “The development of human capital requires keeping an eye on the road ahead, paying particular attention to the future consequences of investment in human capital today.”

Vietnam’s overall HCI score is 0.67, which means that a child born in Vietnam today will be 67 per cent as productive when she grows up and enters the world of work,compared with a child who enjoys complete education and full health.

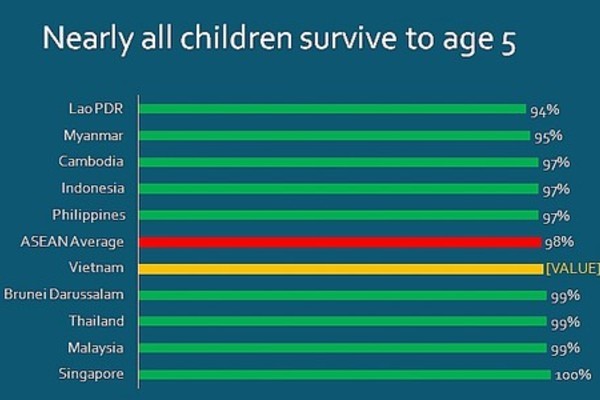

Human capital needs investment today with returns to materialise only in a long time. The HCI contains three different sub-components including the percentage of children surviving to age 5, expected years of learning adjusted for quality of learning, and a measure of health, in this case combining stunting and adult survival.

Vietnam is right at the ASEAN average for the first indicator (child survival to age five). Vietnam comes out especially strong with respect to access and quality of general education. Vietnam’s average years of schooling, adjusted for learning, is 10.2 years. This is second only to Singapore among ASEAN countries.

Vietnam is also among the best performers when it comes to “resilient” students, or those from the lowest quartile of disadvantage who are in the highest quartile of performance.

About 91 per cent of theKinh majority are enrolled in lower secondary, 74 per cent in upper secondary, and then 29 per cent in tertiary education.

|

| Source: World Bank |

In childhood and adolescence, while ethnic minorities children tend to enrol in pre-primary and primary schools at about the same rate as their Kinh peers, they tend to drop out in lower secondary and then much more so in upper secondary. By the time they reach tertiary education age, there is a 30 percentage point gap in enrollment between the Kinh and ethnic minorities. The lack of education reduces access to stable wage jobs with good benefits.

The compounded effect into adulthood is that average measures of the household wealth of ethnic minorities are equivalent to the 5th percentile of the Kinh population.

For the ethnic minority elderly, those who live in rural areas tend to stick with low-value farm work, despite the massive structural transformation taking place in agriculture across Vietnam’s rural regions.

There is a 13 per cent gap between the Kinh and other ethnic minorities in lower-secondary, which widens to 30 per cent in upper secondary, and slightly narrows to 25 per cent in tertiary education.

The bottleneck is that ethnic minorities children do not transition to upper-secondary education and beyond in Vietnam, which in turns reduces their employability.

To narrow the gap between peoples, Vietnam needs to enhance both the quantity and quality of its skilled workforce graduating from universities and vocational education and training institutions, as well as making a smooth transition to the world of work.

If Vietnam follows the current trend, the overall share of the labour force of those above 15 with a tertiary education degree will only marginally increase by 2050.

Tertiary level gross enrolment rate is below 30 per cent, public funding for higher education as a share of GDP is less than 0.5 per cent, and tuition fees as a share of unit cost in public universities is more than 50 per cent. This makes Vietnam one of the countries with the lowest tertiary education enrollment rate, allocating the least amount of public funding, while relying heavily on out-of-pocket contributions.

At the same time, 2018 Global Competitiveness Index ranked Vietnam in the lower segment of 140 countries when it comes to industry-relevant skill sets for university graduates. This low quality of the workforce is reflected in Vietnam’s performance, lagging behind all comparator countries in value-added per employee.

To promote inclusive growth, Vietnam faces a two-pronged challenge in human capital development. The first is to close the gaps in human capital disparities for ethnic minorities. The second challenge is to strengthen overall workforce development and prepare Vietnam for a knowledge-based economy.

These challenges are particularly important as the country embarks on its next socio-economic development strategy for 2021-2030. In order to stimulate systemic tertiary education reforms, universities and vocational education and training (VET) institutions should be held accountable for outcomes, not outputs.

More diversification is needed, including promoting high-quality private tertiary education institutions by allowing equal access to government-funded services and/or research contracts; promoting closer linkages with the world of work; and articulating policies to build bridges and pathways to allow for transfer between VET institutions and universities.

The economic case for investing in education and health is strong in Vietnam. Leveraging the private sector includes tapping into collaborations on the design of tertiary education programmes, enhancing technology transfer, and mobilising funding from enterprises. Technology can also be harnessed to improve skills development itself, for example by using more sophisticated adaptive learning methods to shift towards personalised learning. VIR

Even though the human capital index (HCI) of Vietnam exceeds the global, regional, and even upper-middle-income country averages, Vietnam still faces challenges in ensuring high-quality human resources.

Even though the human capital index (HCI) of Vietnam exceeds the global, regional, and even upper-middle-income country averages, Vietnam still faces challenges in ensuring high-quality human resources.