Throughout the economic reform era, a key policy challenge for Vietnamese leaders has been to continually provide new employment opportunities for the country’s workforce

|

| Edmund Malesky Professor, Duke University and Lead researcher of the Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index |

Rising labour costs and tightening labour markets, combined with pressure from international competitors and demands from international buyers, has led many companies to contemplate enhancing productivity by investing in labour-saving automation. Social distancing within the workplace as a response to COVID-19 may exacerbate interest in these technologies, as companies seek to maximise the productivity of their employees with limited space. Not all forecasts are so gloomy, however; others argue that automation can enhance employment by diversifying businesses’ activities.

This year, the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI) research team attempted to shed light on this debate within Vietnam by asking businesses about their current use and plans for automation in their manufacturing and service sector operations. We defined automation broadly as three sets of activities.

First, using industrial robots in product assembly, distribution, and/or delivery; digitalisation of production or services, such as the use of iPads or tablets for taking customer orders or for back-office activities to reduce error from human input; and adoption of AI, such as autonomous delivery vehicles.

We can use that data to answer three questions: What is the extent of current automation in Vietnam? What factors are driving the adoption of these new technologies? And what is the potential impact on the scale and composition of employment in foreign and domestic businesses?

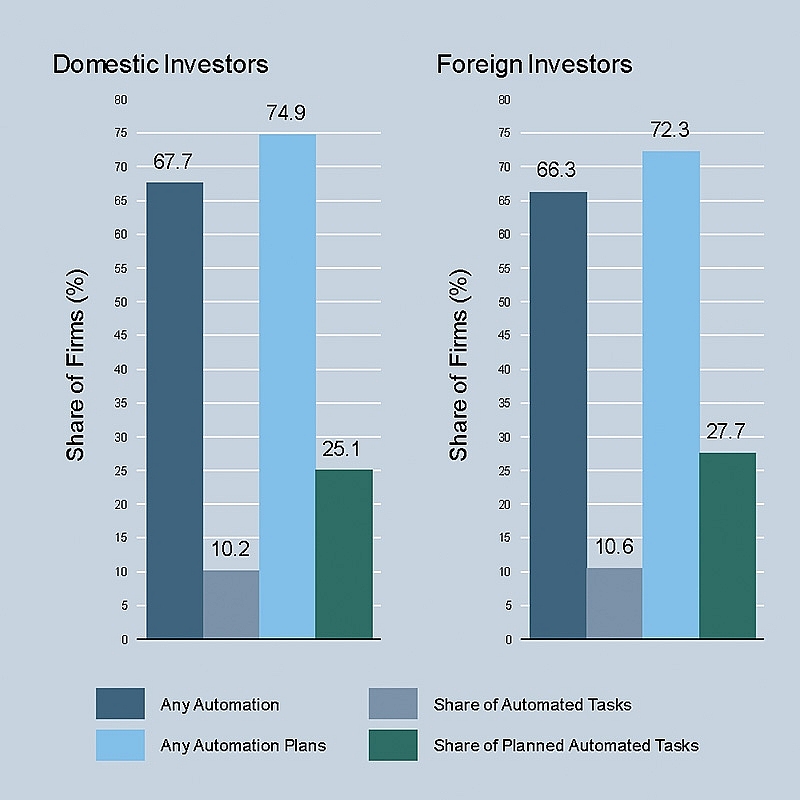

Starting with the first question, the extent of current and planned automation in Vietnam is higher than expected. Within the past three years, 67 per cent of both foreign and domestic investors have automated some operations, while 75 per cent plan to automate new tasks during the next three years over the next three years. Domestic ones claim to have already automated about 10 per cent of their operational tasks over the past three years and plan to automate over 25 per cent of their work in the near future. Automation among foreign firms is only slightly more advanced (10.6 and 28 per cent of current and planned tasks, respectively).

We can see the motivations behind businesses’ automation decisions. They are investing in automation for two reasons. They seek to reduce the costs of labour recruitment and training, and they believe these efforts will assist them with global integration, connecting them to overseas buyers and customers. For domestic businesses, the highest levels of current automation are found among those whose primary customers are foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) based in Vietnam.

However, those selling to third-party buyers have the greatest plans for automating technologies. Foreign businesses that are part of multinational corporations or sell to third-party buyers have been the most ambitious automators. In further econometrics analysis of foreign businesses in the PCI report, we also identified an important third correlate of investment in automation - labour unrest. Businesses that have observed labour strikes among competitors in similarly situated provinces and industries are significantly more likely to adopt automation than those where strikes have been less prominent.

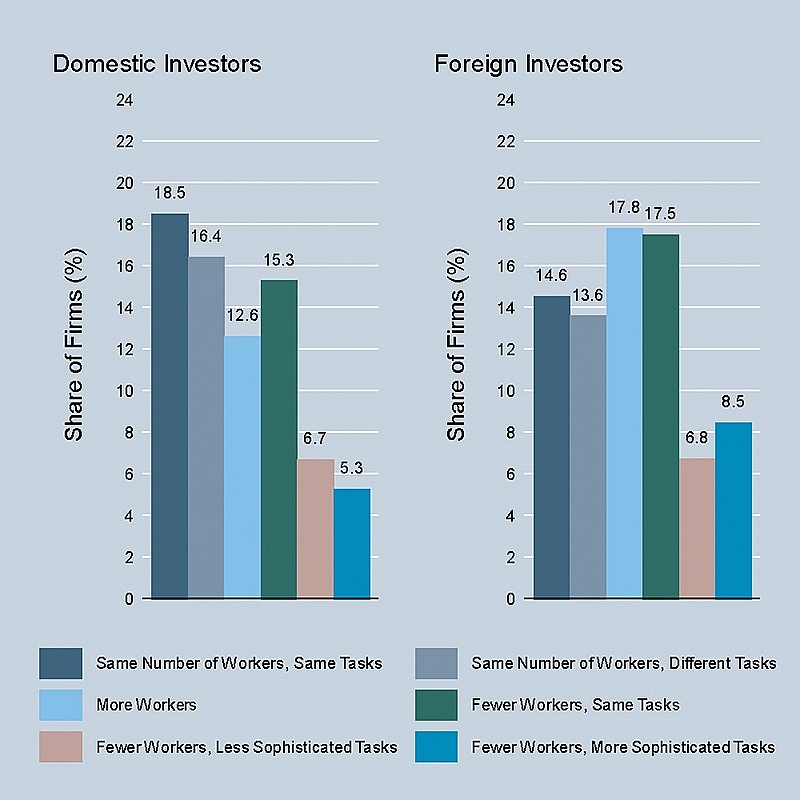

Automation is affecting businesses’ employment decisions in surprising ways. The impact of increased automation on current employment and future hiring plans is diverse and dual-edged. Some 12.6 per cent of domestic businesses have increased employment as a result of automation, compared to 35 per cent who plan to maintain employment at current levels and 27 per cent of domestic businesses who intend to reduce employment. Of this latter group, over half (15 per cent) plan to do the same activities but with a smaller number of people.

|

| Frequency and depth of automation among Vietnamese businesses |

|

| Drivers of automation |

|

| Impact of automation on employment decisions |

By sharp contrast, 17.8 per cent of FIEs expressed their intention to increase employment. This is positive news. Although 33 per cent do still plan to reduce employment, in contrast to domestic investors, a significant share (8.5 per cent) intend to increase the sophistication of their smaller labour forces. Automation is quite diverse across sectors, revealing the dual-edged nature of automated technologies. In some cases, they will lead to redundancies and decreased employment. In other cases, they will lead to enhanced training and greater opportunities for the next generation’s workers.

- We continue to employ the same number of workers, performing the same tasks.

- We employ the same number of workers, but they perform different tasks.

- We have both expanded employment and automated production.

- We employ fewer workers to perform the same number and type of tasks.

- We employ fewer workers, and they perform less sophisticated tasks.

- We employ fewer workers, but they perform more sophisticated tasks.

The impact of automation on the average skill level of companies’ labour forces will be diverse. For domestic businesses, the most frequent answer was that automation would have no impact on the average skill level of employees (just under 24 per cent). The second most common answer for domestic businesses was that they would seek more high-skilled labour (19 per cent), illustrating that some businesses are interested in upgrading their workforces. For foreign businesses, these answers are reversed.

More than 23 per cent of FIEs plan to hire workers with greater skills and just over 20 per cent do not expect to change. This is illustrative of the dual-edged nature of automated technologies. In some cases, they will lead to redundancies and decreased employment. In other cases, they will lead to enhanced training and greater opportunities for the next generation’s workers.

Given that automation is an unstoppable force that is likely to be undeterred by regulatory changes, what can Vietnamese policymakers do to mitigate the harmful effects of new business technologies while simultaneously aiming to take advantage of the opportunities that automation provides? The first recommendation is simple – Vietnamese authorities should double-down on their current legislative achievements in education and labour relations. Make sure these laws are implemented quickly and aggressively, and that, in so doing, bureaucrats adhere to the spirit envisioned by the laws’ architects. The Law on Education and accompanying national curriculum reforms were aimed at enhancing the quality of general and vocational education with the specific goal of improving the skill sets for Vietnamese workers to succeed in an advanced economy.

The Labour Code broke new ground for working conditions and employee-labour relations. Both the Law on Education and the Labour Code were legislative achievements, but the corresponding implementing regulations and decrees at both national and local levels have yet to be written. By augmenting the skillsets of Vietnamese employees and reducing misunderstanding between workers and employers, successful execution of both laws will help mitigate any hurt stemming from firm-level automation decisions.

According to the PCI data, only 29 per cent of foreign employers and 27 per cent of domestic employers assess the workforce near where they do business in Vietnam as fully sufficient to meet their needs. The cost of retraining employees in-house is the largest contributor to their automating decisions, as businesses have justifiable concerns about investing in training when those workers can so easily move on to competitors.

To date, robots have proved more loyal. Better matching general and vocational educational training to business needs will reduce some of the current demands for automation and will prepare Vietnamese workers for better and higher paying jobs both now and after automation occurs. Because it will be extremely difficult for Vietnamese leaders to anticipate what new jobs will be created due to automation, it is important to focus education on providing sets of fungible skills that allows workers to adapt quickly, learn new skills easily, and take advantage of technological change.

At the same time, allowing for more constructive conduits between workers and businesses will provide opportunities for collective decision making about how best to prepare local workforces for automation. VIR

Edmund Malesky (Professor, Duke University and Lead researcher of the Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index)

Are robots coming to take Vietnamese jobs? Are iPads invading Vietnamese workplaces?

Are robots coming to take Vietnamese jobs? Are iPads invading Vietnamese workplaces?