|

|

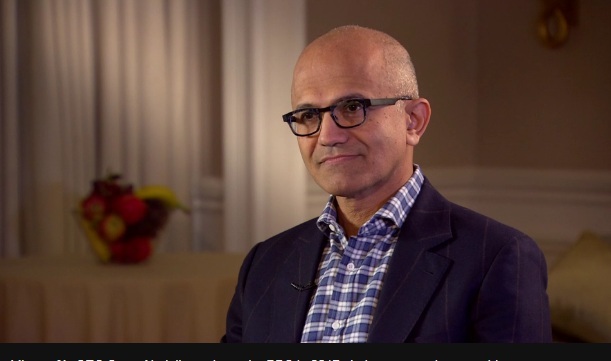

Microsoft's chief executive Satya Nadella |

But, as US-China relations continue to sour on issues of trade and cyber-security, the decades-long ties Microsoft has in China are coming under close scrutiny.

In an interview with BBC News, Microsoft's chief executive Satya Nadella has said that despite national security concerns, backing out of China would “hurt more” than it solved.

“A lot of AI research happens in the open, and the world benefits from knowledge being open,” he said.

"That to me is been what's been true since the Renaissance and the scientific revolution. Therefore, I think, for us to say that we will put barriers on it may in fact hurt more than improve the situation everywhere.”

Microsoft’s first office in China was opened by founder and then-chief executive Bill Gates in 1992. Its main location in Beijing now employs more than 200 scientists and involves over 300 visiting scholars and students. It is currently recruiting for, among other roles, researchers in machine learning.

In April, it was reported by the Financial Times that Microsoft researchers were collaborating with teams at China’s National University of Defence Technology, working on artificial intelligence projects that some outside observers warned could be used for oppressive means.

Speaking to the newspaper, Republican Senator Ted Cruz said: “American companies need to understand that doing business in China carries significant and deepening risk.”

He added: "In addition to being targeted by the Chinese Communist party for espionage, American companies are increasingly at risk of boosting the Chinese Communist party’s human rights atrocities."

Technology as weapon

Mr Nadella acknowledged that risk.

“We know any technology can be a tool or a weapon,” he told the BBC.

“The question is, how do you ensure that these weapons don't get created? I think there are multiple mechanisms. The first thing is we, as creators, should start with having a set of ethical design principles to ensure that we're creating AI that's fair, that's secure, that's private, that's not biased.”

He said he felt his company had sufficient control over how the controversial emerging technologies are used, and said the firm had turned down requests in China - and elsewhere - to engage in projects it felt were inappropriate, due to either technical infeasibility or ethical concerns.

“We do have control on who gets to use our technology. And we do have principles. Beyond how we build it, how people use it is something that we control through Terms of Use. And we are constantly evolving the terms of use.

"We also recognise whether it's in the United States, whether it's in China, whether it's in the United Kingdom, they will all have their own legislative processes on what they accept or don't accept, and we will abide by them.”

'Leaves me wondering...'

Matt Sheehan, from the Paulson Institute, studies the relationship between California's technology scene and the Chinese economy. He said Microsoft's efforts, particularly its Beijing office, have had tremendous impact.

"It dramatically advanced the field, advances that have helped the best American and European AI research labs push further," he said.

"But those same advances feed into the field of computer vision, a key enabler of China's surveillance apparatus."

He cites one particular paper as highlighting the complexity of working with, and within, China. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition, published in 2016, was a research paper produced by four Chinese researchers working at Microsoft.

According to Google Scholar, which indexes research papers, their paper was cited more than 25,256 times between 2014-2018 - more than any other paper in any other field of research.

"The lead author now works for a US tech company in California," said Mr Sheehan, referring to Facebook.

"Two other authors work for a company involved in Chinese surveillance. And the last author is trying to build autonomous vehicles in China.

"What do we make of all that? Honestly, it leaves me - and I think it should leave others - scratching their heads and wondering." BBC

Microsoft does more research and development in China than it does anywhere else outside the United States.

Microsoft does more research and development in China than it does anywhere else outside the United States.