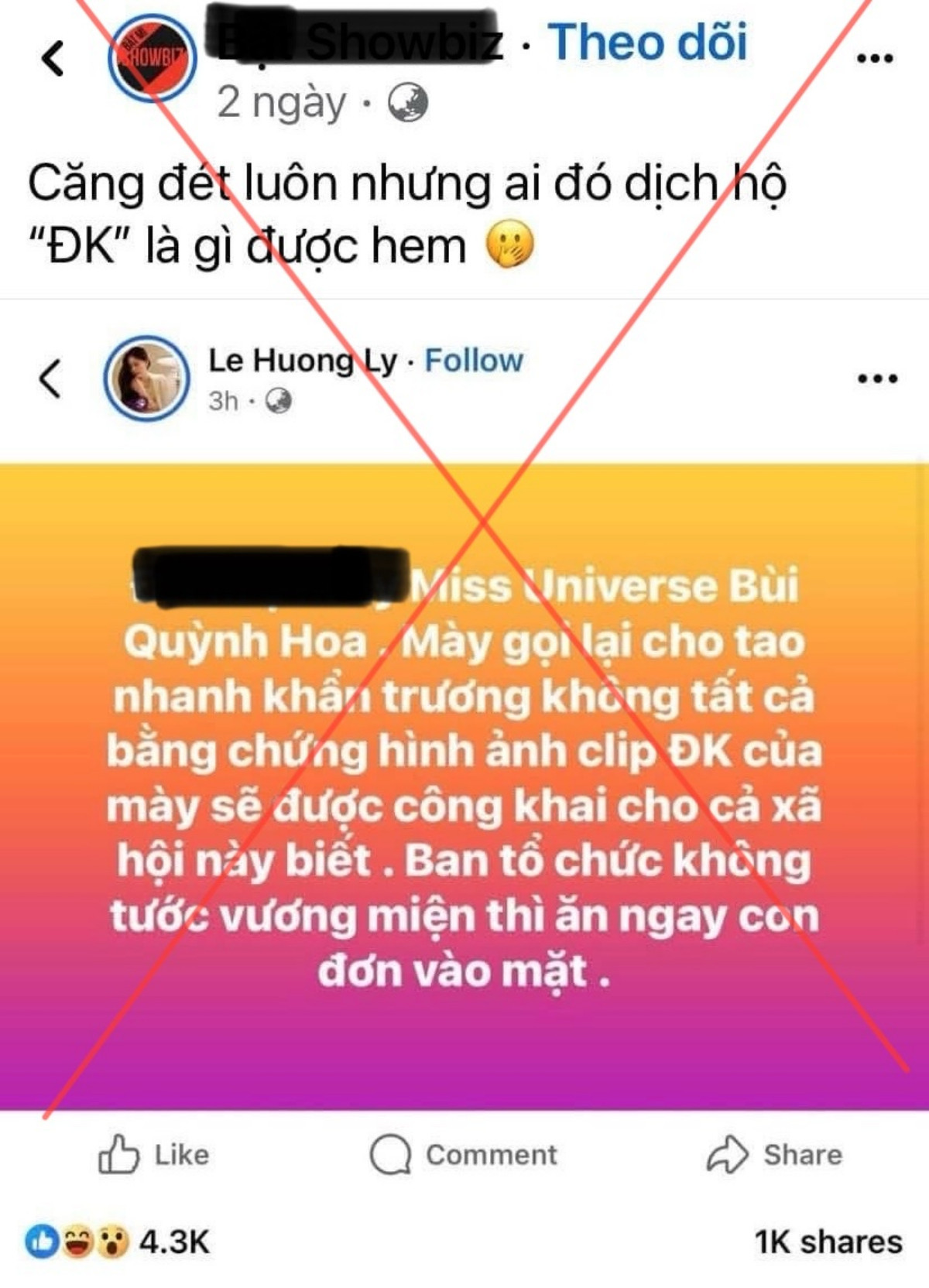

On September 19, Hanoi Police prosecuted Le Huong Ly, 28, residing in Dong Da ward, for defamation, just one day after launching a criminal case. It began from a personal conflict on September 12: Ly posted defamatory content about beauty queen Quynh Hoa on social media, including sensitive statements and vulgar language.

The police assessed Ly’s posts as "untrue, seriously insulting to dignity and honor, and causing harm to the legitimate rights and interests of another person."

The content posted by Ly was shared by hundreds of Facebook fan pages and numerous TikTok accounts, rapidly and widely spreading across platforms.

Many users, seeing the content flood the internet, liked, shared and commented on the false information without hesitation.

Le Quoc Vinh, Chair of Le Bros, said this phenomenon occurs because fake news, unlike truthful information, is designed to deceive and easily fool people.

Fake news often starts with a real event or phenomenon, then gets embellished with exaggerated details, conspiracy theories, and fabrications, causing social confusion.

People see a few seemingly clear events, are misled into believing the entire story is true, and hastily like, comment, or share, inadvertently or deliberately enabling the spread of falsehoods.

For example: one electric vehicle catches fire. Without caring about its cause, the purveyor of fake news inflates the message by saying that the products of the brand are “extremely dangerous,” prone to catching fire, and have additional hazards.

Vinh noted there are two English words tied to “truth.” First is ‘reality’, which denotes what objectively happens. Second is ‘truth’, which refers to what we believe is right, based on knowledge, views, and beliefs. Ironically, “reality” and “truth” are not always aligned, and sometimes they conflict.

Vinh argues that fake news only spreads when it strikes people’s prejudices. If you already harbor bias against an individual, company, or product, then a small kernel of “reality” in a fake claim may be enough for you to leap to believe it, and perhaps act to propagate it without verifying.

“Thus, when we share, comment, or even click ‘like’ or ‘haha’, we directly or indirectly help that false information spread, pulling more people in our network to read and further propagate it,” Vinh said.

Even posts or articles that talk about the existence of a fake news item, but don’t clearly and transparently state it’s false, or don’t mark manipulated images with red crosses, allow the fake news to continue spreading. That is because users often receive information superficially. They latch onto a few keywords or phrases that align with their bias and immediately become transmitters themselves.

Vo Quoc Hung from Tonkin Media notes that Vietnamese users tend to engage more with emotionally charged content, such as drama, anger, and fear, and fake news exploits these triggers thoroughly.

When fake news appears, users rarely or never verify sources. The FOMO (fear of missing out) mindset pushes them to spread it. This is a matter of awareness.

Hung suggests the economic incentive behind spreading fake news via fake accounts and fan pages on platforms like Facebook or YouTube is enormous: when a post goes viral and gains a huge view count, the ad revenue generated can be sizable.

The development of technology also facilitates the spread of fake news. According to Statista, bots and fake accounts make up nearly 40 percent of interaction triggers and fake news propagation in Vietnam.

Meanwhile, laws are present but not strong enough, making it very difficult to fully deal with fake news, especially cross-border fake news that's nearly impossible to control.

Digital expert Nhan Nguyen thinks that Vietnamese users have strong information consumption needs, but lack personal ‘filters’, so they easily fall for sensational content, which is why fake news thrives and spreads.

The Digital 2025 Vietnam report by We Are Social and Meltwater aggregates data on Vietnamese Internet users’ behavior.

By early 2025, Vietnam had 79.8 million Internet users, with Internet penetration of 78.8 percent of the population.

Analysis by Kepios shows that from January 2024 to January 2025, the number of Internet users in Vietnam grew by 223,000 (+ 0.3 percent). By January 2025, Vietnam had 76.2 million social media accounts, equivalent to 75.2 percent of the population.

On average, Vietnamese users spend 6 hours 5 minutes per day on online activities. Over 2 hours are spent on social media, led by Facebook, Zalo, and TikTok.

Le My