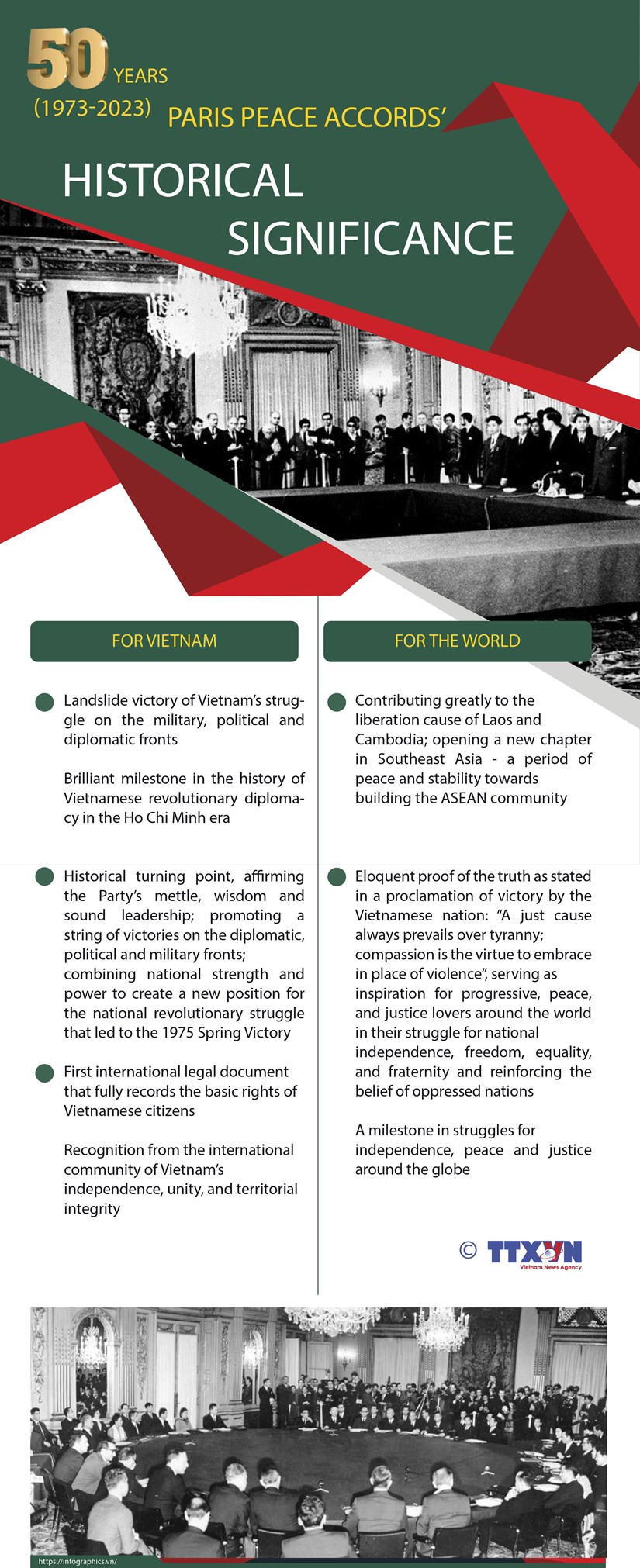

The signing of the Paris Agreement on ending the war and restoring peace in Vietnam on January 27, 1973, was a resounding victory of Vietnam’s revolutionary diplomacy in the Ho Chi Minh era, making important contributions to the common victory of the whole nation and, at the same time, leaving invaluable diplomatic lessons, including those related to national independence and international solidarity.

Vietnam’s anti-American resistance war and national liberation fight as well as negotiations at the Paris Conference took place in a very complicated historical context. It was at a time when the system of the socialist countries had taken shape and grew stronger and stronger, actively helping the world revolutionary movement, including the Vietnamese revolution.

But within the socialist bloc, there were different views on the way to build socialism and fight for national liberation, and even sharp conflicts arose. On the other hand, the enemy of the Vietnamese people were the US imperialists with strong economic and military potential.

With lessons drawn from the anti-French resistance war, the Central Committee of the Vietnam Workers’ Party upheld the spirit of independence, self-reliance and international solidarity in both resistance and negotiation guidelines. These were the two basic guiding points that run through the entire negotiations at the Paris Conference from the beginning to the end.

From 1965 to the end of 1966, the US imperialists both escalated the aggression war against Vietnam and made the “fake peace” argument, asking the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to sit down for negotiations.

In January 1967, the 13th conference of the Central Committee of the Party decided to open a new diplomatic front in order to more strongly denounce the crimes of the US imperialists and expose their peace tricks, uphold the righteous stance of the revolution, and take advantage of the sympathy, support and assistance of the socialist countries and progressive people around the world, including the Americans.

In 1968 spring, the Vietnamese army and people launched a general offensive and uprising throughout the southern battlefield (with urban areas as the main direction), forcing the administration of US President Lyndon B. Johnson to de-escalate the war and agree to sit at the negotiating table with Vietnam at the Paris Peace Conference.

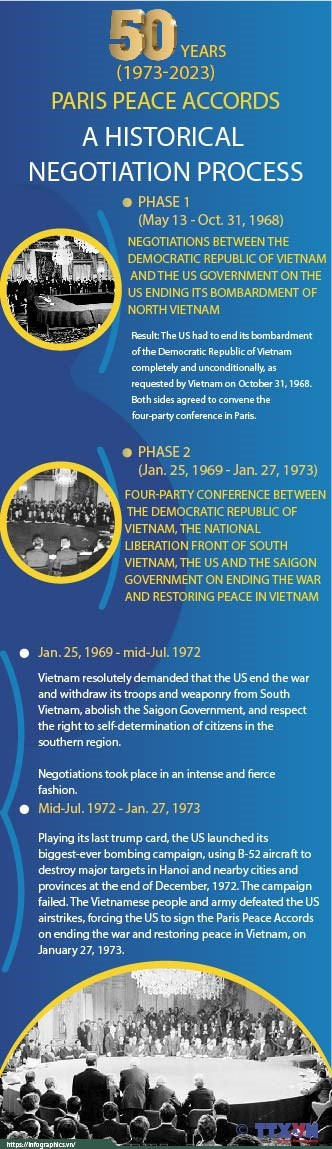

On May 13, 1968, the official negotiations between a delegation of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and that of the US Government began in Paris, marking a new phase of the Vietnam war. Vietnam officially competed on both battlefield and on the diplomatic front, with the motto “fight and talk at the same time”.

Vietnam steadfastly required the US to unconditionally cease its bombing raids and all other war activities against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, while other relevant issues of the two sides would be discussed later. Meanwhile, the US side raised a demand that the North withdraw its troops from the South, and stop sending people and reinforcements into the South.

Conscious of Vietnam’s correct stance and resolute attitude and, at the same time, difficulties and losses on the battlefield, the movement against the war of all classes of Americans increased.

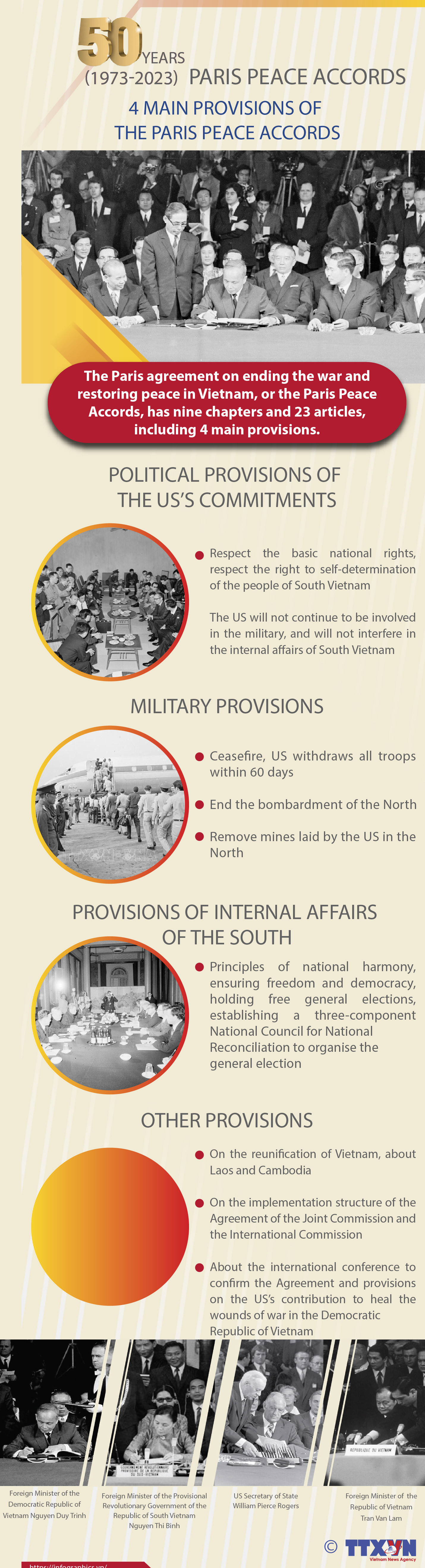

On November 1, 1968, US President Johnson was forced to declare an end to all acts of war against the North of Vietnam. Following the event, the struggle between Vietnam and the US began to revolve around the format and the participants of the conference and came to an agreement to organise a four-party conference, including the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the National Front for the Liberation of the South (then the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam), the US, and the Republic of Vietnam (Saigon administration).

Taking the initiative to step into the situation of “fight and talk” was really a great creativity of the Vietnamese Party, demonstrating independence and self-reliance in terms of policymaking.

In 1969, Richard Nixon was elected as President of the US and proposed a strategy known as “Vietnamisation” of the war, under which the expeditionary troops and those of some allied countries gradually withdrew. The army of the Republic of Vietnam served as the main combatants but were still commanded by the US through a contingent of military advisors and the provision of capital, technical weapons and means of war.

On January 25, 1969, the four-party Conference on Vietnam officially convened its first session. During the negotiations, the Vietnamese side struggled in all aspects related to the war, but focused on the two most important issues, namely demanding for the withdrawal of all US and allied troops from the South and for their respect to the basic national rights and self-determination right of the people of South Vietnam. The demand was supported by many governments around the world.

World public believed that the Vietnamese side had shown goodwill for peace, demanding that the US government soon end the aggression war against Vietnam. At the Paris Peace Conference, Vietnam took advantage of public forums with official speeches and insightful speeches to win public opinions.

The Vietnamese side also attached great importance to the press mobilisation. During the nearly 5 years of negotiations, the Paris Peace Conference held nearly 500 press briefings, seeing them as invaluable opportunities to denounce the stubbornness of the US and the Saigon administration, and at the same time hold up the peace and goodwill stance of Vietnam, actively contributing to the great solidarity of the world people’s front in support of the Vietnamese revolution, and strongly isolating the US – Saigon administration on the international arena.

The great military victories of the Vietnamese revolution on the battlefield (Route 9 – Southern Laos Campaign 1971, Easter Offensive 1972) resulted in heavy losses to the enemy, step by step thwarting the US strategy of “Vietnamisation” of the war, and creating advantages for Vietnam at the negotiating table.

Unable to shake Vietnam’s position at the negotiating table, Nixon intensified military actions on the battlefield. On December 14, 1972, he approved a plan to launch strategic air raids, mainly using B-52 strategic aircraft, on Hanoi and Hai Phong.

With the airstrikes, the US wanted to win military victories and create strength in the negotiations at the Paris Conference, forcing the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to sign an agreement to end the war and destroy the economic potential and defence forces of North Vietnam, especially making big cities unable to support the resistance war in the South. Moreover, the airstrikes were expected to offer more time to the army and administration of Saigon to strengthen their forces and cause panic among the Vietnamese people. Through unprecedented strategic raids and devastating destruction, the US wanted to rattle its military power to the world and deter countries that were struggling against imperialism.

The Paris Peace Conference (1968 – 1973) has forever gone down in the history of the Vietnamese nation in general and the Vietnamese revolutionary diplomacy of the Ho Chi Minh era in particular as a hallmark that never fades. Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement (January 27), Vietnam is more deeply aware of the significance of this special historical document. Many lessons have been learned from the historical negotiations, in which the lesson on upholding the spirit of independence and international solidarity still holds profound theoretical and practical values.

From December 18-29, 1972, the US launched strategic air raids (mainly by B-52s) on Hanoi and Hai Phong but they were a complete failure. The North Vietnamese air defence forces shot down 81 aircraft of all kinds (including 34 B-52s), forcing the US and the Saigon administration to sign an agreement to end the war (January 27, 1973). Accordingly, the US and other countries committed to respect the independence, sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity of Vietnam, withdraw all expeditionary troops and troops of allied countries, and destroy all US military bases. They pledged not to continue military involvement or interfere in internal affairs of the South Vietnam. The parties let the people of the South determine their own political future through free general elections; recognised the actual status quo in South Vietnam with two governments, two armies, two regions of control and three political forces; ceased fire on the spot; and swapped prisoners and captured civilians. With the Paris Agreement, Vietnam “beat the US out”, created favourable conditions to the complete liberation of the South and national reunification in the spring of 1975./.