Easy access to the Internet plus the widespread popularity of cheap electronic gadgets capable of filming, photographing and recording is fertile ground for other people to monitor and interfere in others’ life without the latter’s consent.

|

| The right to privacy in Vietnam has changed considerably. The 2013 Constitution rules that “everybody is entitled to imprescriptible right to personal life.” – SGT Photo: Uyen Vien |

It is more difficult to define the jurisdiction of “the right to privacy” in this digital age if it is juxtaposed with other freedoms, such as freedom of the press, the right to access information and freedom of speech.

Social networks have helped citizens exercise their democratic rights and express their attitude towards social issues. However, some have taken advantage of social media to blatantly violate others privacy, including revelation of personal life, revelation of bank information, defamation, intrusion of mobile phones to extract sensitive images or personal data for sale. The number of handled violations remain humble, though.

Over the years, the right to privacy in Vietnam has changed considerably. The 2013 Constitution rules that “everybody is entitled to imprescriptible right to personal life;” and “nobody is entitled to illegally opening, controlling, or taking hold of and keeping other people’s correspondence, telephones, telegraphs and other forms of information exchange.” These stipulations were later stated in Article 38 of the 2015 Civil Code, which says that “personal life, personal secrets and family secrets are imprescriptible and protected by law,” and “personal life” has a wider scope than “personal secret.”

Despite these conspicuous regulations, privacy in Vietnam is substantially impacted by the local distinctive culture associated with villages where families lived in close proximity and contact allowing virtually no place for freedom of interference.

Moreover, that situation has been influenced by the culture assimilated in the subsidy time when everything was considered collective, which allowed institutions and some individuals to interfere in social affairs and even personal affairs.

This legal ambiguity has resulted in many cases in which violators made use of excuses for their privacy infringements. For instance, they might think or say they did so on behalf of others or hacking personal information was not a violation because the people involved was a “bad one.”

Many have heartily received hacked personal information and shared it, considering themselves “being spared” from such hacks. Others have showed their “power,” when frustrated or angry, by posting statuses or livestreaming content to defame the people they disliked. Some violators have even enticed their friends and others in the community into “boycotting” their victims regardless of effective law provisions.

The result was several victims even so distressed because of these libels or defamations that they committed suicide. On March 11, 2018, a schoolgirl in grade 11 in Nghe An Province killed herself in her yard’s pool, leaving a suicide note that she apologized to her parents for her mistake. The reason for her death was a video clip filming the scene in which she was kissing her male classmate, which had gone viral on social media.

There have been also cases where personal information of Covid-19 patients was posted online against their will and their untrue relationships were traced as if they were “criminals” giving rise to disparaging or offhand comments. Some stories were made up and adversely affected the victims’ legitimate rights and interest.

How are these violations of privacy handled by law

In Vietnam, violations of privacy on social media are treated as follows.

Criminal prosecution. Violators may be subject to the following counts: humiliation (Article 155); libel (Article 156); infringements of the secrecy or safety of correspondence, telephones, telegrams or other forms of personal information exchange (Article 159; however, this article stipulates that one is subject to this count only after he or she has already given administrative or disciplinary punishment and continued to commit the infringement); violations of illegally sharing or using information on the Internet or telecom networks (Article 288).

Administrative punishment. Decree 15/2020/ND-CP rules that (1) fines worth between VND5-10 million will be imposed on individuals who take advantage of social media to conduct one of the following acts: supply and dissemination of fake information, untrue information, defamation and slander to undermine credibility of organizations, institutions and individuals; supply and dissemination of information on promoting bad habits, superstition, obscene and depravation unsuitable to fine customs of the people; (2) fines worth between VND10-15 million will be imposed on acts of revealing personal life and other secrets which are misdemeanors not subject to criminal responsibility. In addition, the responsibility to implement measures for remedying bad consequences can be assumed so that untrue or misleading information must be removed.

The enterprise which owns the social network is subject to fines worth between VND50-70 million if involved with violations, such as active storage or dissemination of fake information, untrue information, defamation and slander to undermine credibility of organizations, institutions and individuals.

In addition, violators may be subject to civil liability as follows: giving compensation of losses in accordance with the Civil Code in case the victim in question submits a lawsuit.

Self-protection and respect for others

The first thing to start with is minimizing the upload of person data on social media. Many have voluntarily and innocently posted plenty of personal and family information on the Internet, such as family photos, children’s academic achievements or even proofs of their properties.

At the same time, Internet users should be aware of others’ privacy. This is particularly important because only when one respects others’ privacy will his or her privacy be respected by others. For example, the principle that a person’s images or information cannot be posted on social networks without his or her consent must be applied. Another case is while visiting a person’s residence, photos of the house or scenes of it must not be posted or livestreamed on the Internet if not permitted. Also, personal information must be double-checked before being posted on social networks.

If one’s privacy is infringed, the people involved should store the proof or request a bailiff to record the proof of violation and send it to the provincial department of communication and information or the police. In severe cases, a lawsuit can be lodged at court in accordance with civil procedures to seek compensation.

Handling of violations too slow

Another legal issue which should be paid adequate attention to at present is citizens’ privacy protection when it comes to the digital environment. This is still relevant although the formation of the legal framework for it continues to be a tough task. In many cases, no sooner had a regulation been introduced than technology was developed to surpass the framework of the regulation. Yuval Noah Harrari wrote in his book “A Brief History of Tomorrow” that “Internet is a free and lawless zone that erodes state sovereignty, ignores borders, abolishes privacy and poses perhaps the most formidable global security risk.”

Basically, Vietnam has the ample legal framework with which violations of privacy can be treated. However, its enforcement is still a problem. The implementation of the concerned regulations requires technical facilities as well as time and efforts of relevant agencies. In plenty of cases, the treatment of violations comes only a very long time after the consequences.

It must be acknowledged, however, that the handling of privacy violations in Vietnam on social media is by no means simple because in many cases, violators use unknown accounts or are from another country. If violators use accounts in Vietnam, the relevant agencies should deal with them quickly and forcefully to deter similar infringements.

If violators utilize overseas accounts, the relevant agencies should immediately support the victims to minimize bad consequences, such as proposing communication firms removing related personal information or sending out messages roundly condemning such violations of privacy.

Dr. Thai Thi Tuyet Dung

University of Economics and Law under the Vietnam National University – HCMC

Source: SGT

Solutions for using, managing livestreams

The state needs to resolve disputes about social networks by law. This is the solution of a modern society that respects a rule-of-law culture.

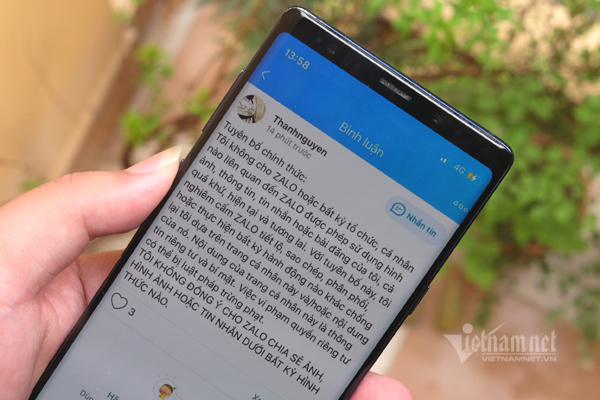

Users object to Zalo’s use of their images and personal data

Many Zalo users are sharing posts regarding their claims about the right to use personal data. They do not want Zalo to collect and use personal images and data when they use this social network.