|

| Quan Le |

Quan Le, founder of Binkabi.io, provided an insight on how blockchain could improve efficiency and fairness in the global agriculture supply chain by helping farmers to gain better access to market and funding.

Do you ever wonder where the coffee you drink in the morning, the rice you eat at lunch, or the cashew in your favourite snack comes from? Chances are they were produced by one of the 500 million farmers in developing countries, and reached you through a long and complex supply chain. Whether the farmer comes from Vietnam (coffee), Thailand (rice), or as far away as the Ivory Coast (cashews), they are likely to share one thing in common: an unfair share of profits generated from over a trillion US dollars in global trade of agricultural commodities.

Why is this the case? The answer lies in the nature of competition along the commodity supply chain. The further downstream (closer to consumers) a player is, the greater the bargaining power. So the retailer has more bargaining power than the wholesaler or distributor, who in turn has more power than the importer, exporter, processor, aggregator and so on. The smallholder farmer, being at the most upstream position in the supply chain, often is the most vulnerable to any commodity price shock.

The commodity supply chain as a whole has been on a downturn since 2011. The Bloomberg Commodity Index has dropped from 176 in 2011 to 77 this month. Whilst all in the supply chain have suffered to varying degrees, farmers, especially those in developing countries, have borne the brunt of the downturn. When coffee commodity price falls, consumers do not pay less for their coffee drinks but farmers receive less for their beans. So at present, the system discriminates against farmers, the very actor who makes it possible in the first place.

Power in the international agriculture supply chain also correlates to the size of the players. A quarter of global agrifood trading is handled by the ABCD (ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus). These groups, together with smaller Asian cousins NOW (Noble, Olam, and Wilmar) and national giants such as China’s Cofco and BRF of Brazil, control hard-to-replicate networks of silos, ports, ships, and trucks to buy in surplus and sell to customers worldwide. These groups, many of them are family-based or state-owned enterprises, also have information power to their advantage: supply disruptions (due to weather, for example), shipping data, and demand changes.

|

How blockchain works There are five basic principles underlying the technology. 1. Distributed database Each party on a blockchain has access to the entire database and its complete history. No single party controls the data. Every party can verify the records of its transaction partners directly, without an intermediary. 2. Peer-to-peer transmission Communication occurs directly between peers instead of through a central node. Each node stores and forwards information to all other nodes. 3. Transparency with pseudonymity Every transaction and its associated value are visible to anyone with access to the system. Each node, or user, on a blockchain has a unique 30-plus-character alphanumeric address that identifies it. Users can choose to remain anonymous or provide proof of their identity to others. Transactions occur between blockchain addresses. 4. Irreversibility of records Once a transaction entered into the database, records cannot be altered, because they are linked to every record that came before them. Various computational algorithms and approaches are deployed to ensure that the recording on the database is permanent, chronologically ordered, and available to all others on the network. 5. Computational logic The digital nature of the ledger means that blockchain transactions can be tied to computational logic and in essence programmed. So users can set up algorithms and rules that automatically trigger transactions between nodes. (Source: Harvard Business Review)

|

|

|

In recent years, many have diversified from downstream trading to more upstream activities such as processing, or even farming. There is another little-known but profound reason to a smallholder farmer’s vulnerability – their cash flow cycle. Being typically poor, farmers have to borrow, in one form or another, to buy inputs like seeds, fertiliser, and chemicals at the beginning of their crop cycle. At harvest, they immediately have to sell crops to repay the loan. With everyone selling to a few buyers, the price is often depressed at harvest unless of course it is a poor harvest and there is not much to sell. In either case, small-holder farmers do not gain much from their labour and the vicious circle of borrowing at growing and selling at harvest perpetuates.

Only players with a large asset base and established relationship with banks can obtain finance. Other smaller players such as aggregators and farmers are cut off from funding or have to borrow at extortionately high rates. Supply chain assets are often not easily converted into cash, and banks lack visibility and information to be able to assess supply chain credit risks properly. Many banks simply see farmers as not worth the effort.

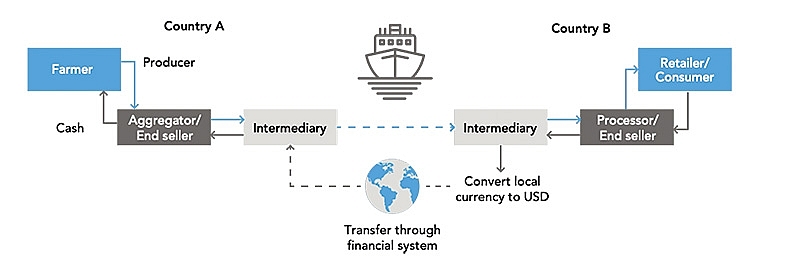

Due to lack of trust, most international trade is conducted through intermediaries who typically charge between 10-30 per cent, depending on the degree of supply chain integration. For example, the multi-billion-dollar trade flows between Vietnam and Africa in rice, fish, cotton, and cashew nuts are mainly carried out through intermediaries. Intermediaries play an important role in providing trust in supply chains but the question is what is the fair price of that trust? More for intermediaries could mean less for farmers.

Besides, not much has changed for centuries in that international trade is surprisingly still paper-based. Errors and fraud are common – for example counterfeiting bills of lading to take delivery of goods, or receiving payment without sending the goods.

Binkabi has developed a blockchain-based agriculture trading and financing platform to address the challenges outlined above. Binkabi is creating a vibrant network of marketplaces of commodities and supply chain finance consisting of banks, commodity exchanges, warehouse providers, transporters, farmers, aggregators, and processors.

The Binkabi platform uses smart contracts on the blockchain (see box) to secure and automate commodity trading and financing. Upon depositing commodities for sale at one of the accredited warehouses, the seller will receive a warehouse receipt representing ownership of the commodity. Meanwhile, the buyer needs to send the required payment to a partner bank. The Binkabi platform, which connects with both accredited warehouses and banks, swaps the warehouse receipt with the payment in one single transaction. The buyer ends up with warehouse receipt and the seller the cash. The buyer can then redeem the receipt for physical commodity or sell on to another user.

With Binkabi’s smart contracts, the transaction is 100 per cent secured. If either party fails to perform then the transaction is cancelled, and the digital asset returns to the original sender. The transaction is also very fast: an entire trade cycle from posting an order to agreeing a contract to settlement typically takes less than five minutes. For farmers it means a near instant receipt of cash in their bank accounts, instead of days or weeks.

In a lending transaction, a borrower would “lock’ warehouse receipts in a smart contract vault giving the bank the confidence to lend. The entire process of securing warehouse receipts, disbursing funds, monitoring performance and managing repayments is automated through the Binkabi platform. This helps banks to dramatically reduce operational costs and credit risk which, in turn, translates into lower borrowing costs for farmers and SMEs and overall a much faster service.

The Binkabi technology has a wide range of uses. Farmers at harvest can choose to store commodities in warehouses, borrow against them whilst waiting for better prices to sell. A commodity aggregator could conveniently borrow from a bank on the Binkabi platform to supply to a large processor under a long-term contract, enabling all actors in the supply chain to achieve more efficient working capital management. Ultimately, it is about helping farmers and small- and medium-sized enterprises in emerging markets to benefit more from their production through a fairer allocation of profits along the agriculture supply chain. VIR

Embracing potential for an effective supply chain system

Having in place an inclusive supporting industry is vital for the country to boost the competitiveness of Vietnamese-made products in the global market.

Vietnamese SMEs shown how to enter global supply chains

Vietnam is among the top countries attracting FDI in the Asia-Pacific region, but the rate of domestic SMEs participating in the value chains of foreign-invested companies is rather low.

More supply chains to shift to Vietnam, ASEAN

Southeast Asia, especially Vietnam, can expect to see more supply chains coming its way if it improves production technology and capacity, as well as regional cooperation, HSBC officials have said.

A fair and efficient supply chain plays an important role in the development of any sector.

A fair and efficient supply chain plays an important role in the development of any sector.