|

| By Jacques Morisset - Lead economist and programme leader for Vietnam World Bank |

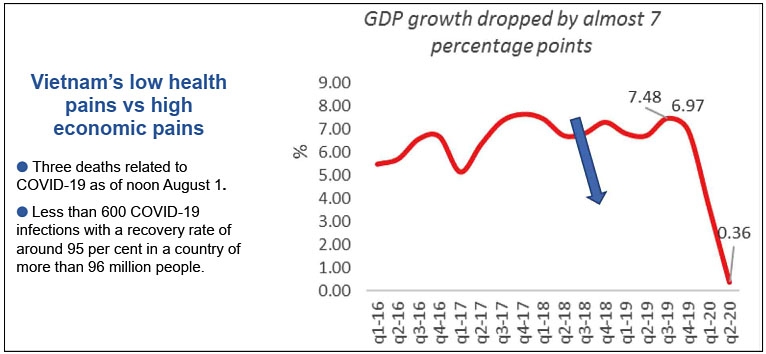

The country’s GDP was still growing at a 0.4 per cent in the second quarter of 2020, but it was the worst performance recorded over the past 35 years. The magnitude of the economic slowdown, a drop of almost seven percentage points, was equivalent to the one observed in most affected countries – except that Vietnam’s economy, like a healthier body, was in a better initial position to resist the pandemic.

The magnitude of the COVID-19 shock might have been bigger than captured by the slowdown from the perspective of jobs and income. The authorities estimate that over 30 million Vietnamese workers – approximately half of the labour force – were affected at the height of the lockdown during the month of April.

The Ministry of Labour, Invalids, and Social Affairs also reported that urban unemployment rose by 33 per cent during the second quarter, while the average income per worker decreased by 5 per cent. Granted, thanks to the easing of social distancing since late April, most family businesses have resumed their activities, and almost all wage workers are back to work, according to a recent phone survey conducted by the World Bank Group.

However, one can argue that the economic shock has been unexpectedly large for a country used to recording full employment during the last two decades.

Looking ahead, Vietnam’s economy remains vulnerable to new waves of coronavirus outbreak and, even in their absence, it could be stuck in what we can label as the “COVID-19 economic trap.”

In the immediate future, we believe that the Vietnamese economy will not be able to fully rely on its two traditional drivers of growth – foreign demand and private consumption. Given the uncertainties in the domestic and international contexts, risk-averse households will limit their investment and consumption plans, while exporters will continue to suffer from international mobility restrictions and falling global income.

|

For example, the tourism sector is likely to miss the 20 million foreign travellers that were expected to visit Vietnam in 2020. The export manufacturing industry will face a further decline in orders from abroad. All manufacturing exports – with the notable exception of computer parts – have contracted in the past six months.

According to the World Bank’s latest economic update on the new normal for Vietnam, the country is nonetheless in a good position to escape this economic trap for at least two reasons.

Firstly, the government has created enough fiscal space to implement an ambitious fiscal stimulus. At the end of 2019, the level of public debt to GDP ratio was about 7 per cent – lower than in 2016 – and the authorities had accumulated massive cash reserves. The government can therefore enhance both the aggregate demand in the short term and the aggregate supply in the longer term by spending more and better.

Of course, such a tool should be used with caution to maintain fiscal and debt sustainability over time. It will also require an effort to improve the allocative and financial efficiency of public expenditures. The positive impact associated to the fiscal stimulus can be maximised only if the authorities are capable of selecting and rapidly implementing the projects with the highest multiplier effect on jobs and the entire economy.

Concurrently, to further stimulate the aggregate demand, this fiscal drive should also provide smart support to the private sector through tax relief and financial assistance.

Because Vietnam’s performance has been uneven in these aspects, our economic update offers a series of recommendations on how to improve them. While the fiscal stimulus can boost Vietnam’s economy in the short term, the return to the pre-crisis trajectory of sustained and inclusive growth might require more effort.

Fortunately, the country can count on a second, and perhaps unique, advantage. By staying ahead of the curve in the fight against the pandemic, Vietnam can increase its footprint on the world economy by attracting foreign businesses that are now looking to diversify their activities and mitigate the risks.

Vietnam can also diversify its trade by forging alliances with countries that have also low rate of infections, while exporting rice and other agriculture products to the increasing number of countries facing higher food insecurity. On the domestic front, Vietnam can accelerate contact-free, digital services such as e-learning, e-commerce, e-government, and telemedicine.

Such a move will help meet the growing demand for quality services by the emerging middle class and also improve the country’s competitiveness.

Escaping the COVID-19 economic trap has become the priority for Vietnam, as it will be for many other countries. Vietnamese policymakers have the opportunity to move faster than others. Not only can this opportunity help Vietnam adapt its own economy to the new realities, but also inspire other governments in their efforts to define what will be the new normal in the post-pandemic world. VIR

Jacques Morisset