Low investment in technological innovation and human resources development could be undermining the competiveness of the Vietnamese economy and businesses, especially amid the country’s drive towards the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Analysts warn that Vietnam must do more to avoid becoming a low-tech dumping ground

The Ministry of Planning and Investment’s (MPI) General Statistics Office recently conducted a survey on Vietnamese manufacturing and processing innovation levels for the 2012-2017 period, on the threshold of Industry 4.0 penetrating the country.

Results showed that domestic business spending on research and development (R&D) remains limited, with an average 6.5 per cent of enterprises engaging in R&D.

“This is in line with the fact that over 97 per cent of local businesses are small- and medium-sized. They lack capital, skills, technology, and modern machinery, so they cannot conduct R&D,” said Luong Van Khoi, vice director of the MPI’s National Centre for Socioeconomic Information and Forecast.

Low R&D

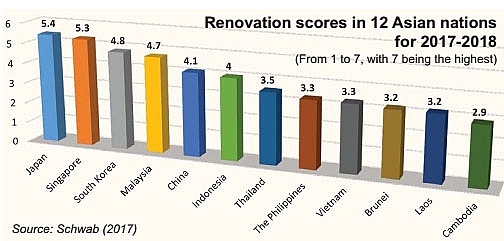

According to the Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018 by the World Economic Forum, Vietnam remained at a medium level in Southeast Asia in terms of innovation, equal to the Philippines and above only Brunei, Laos, and Cambodia. Vietnam’s scores have remained almost the same over the past five years, with a slight rise from 3.1 to 3.3.

Under a survey on science, technology, and innovation in Vietnam conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Bank, the country’s gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD) occupied only 0.2 per cent of the GDP. Meanwhile, the rate is about 3.7 per cent for South Korea, 3.3 per cent for Japan, 1.8 per cent for China, and 0.8 per cent for Malaysia.

GERD includes expenditure on R&D by enterprises, higher education institutions, as well as government and private non-profit organisations.

In Vietnam, private companies occupy about 15 per cent of the country’s total R&D investment, while nearly 70 per cent comes from the government and the rest from higher education institutions.

In comparison, private R&D investment is nearly 80 per cent in Japan, 75 per cent in South Korea, 73 per cent in China, 70 per cent in Malaysia, 62 per cent in Singapore, 58 per cent in the Philippines, 45 per cent in Thailand, and 38 per cent in Laos.

According to Phan Hong Mai, an economist from the National Economics University in Hanoi, in Vietnam, domestic businesses are aware of the importance of innovation, but they mainly focus on this regard in terms of improving product quality.

“Basically, it means that they attempt to make better old products rather than comprehensively improve the process from product design to distribution. Concurrently, Vietnamese businesses simply upgrading products will not help to create new global products, and will not lead to a rise of Vietnam’s position in the global value chain,” Mai said.

According to the World Bank, the percentage of Vietnamese businesses using quality certification is very low, at only 9 per cent, while that of foreign counterparts is 50 per cent.

In reality, innovation is a crucial mission for Vietnamese enterprises, in which R&D is particularly necessary to be invested. R&D investment can help businesses improve their competitiveness significantly.

For instance, Rang Dong Light Source and Vacuum Flask JSC was once on the brink of bankruptcy. However, it rose to become one of the 500 biggest Vietnamese enterprises within 10 years, thanks to the application of high-technologies and workforce training.

Rang Dong now contributes more than $10 million to the state budget. Last year, the company’s revenues totalled VND3.62 trillion ($157.4 million), with its profit augmented by 25 per cent against the initial plan, and average employee income climbing 6.2 per cent on-year.

Former Minister of Science and Technology Nguyen Quan said, “Enterprises like Rang Dong are unfortunately rarely found. In general, technological innovation in Vietnamese enterprises, and human resources improvement, remains very weak.”

Low HR investment

According to the National Economics University’s recent survey involving 583 local enterprises from six big cities in Vietnam, only 9 per cent had a human resources policy lasting over three years. A quarter had a relevant policy for less than three years, and 66 per cent did not have one at all.

The respondents also fail to place big investment on innovation, and training on innovation due to a limited budget.

Since 2011, half of them have spent from VND1.1-3 billion ($47,800-$130,400) mainly on technology transfer, consultancy, and working materials. About 4 per cent has spent over VND10 billion ($434,800) on innovation.

Most of the surveyed businesses did not have a long-term budget for training in innovation and budgets over the next few years seem to be falling. Regarding training content and topics, only 30 per cent of respondents organised training for innovation for employees.

“Low investment in R&D has been stunting competitiveness for Vietnamese businesses. According to global innovation rankings, Vietnam is placed 76th out of 142 countries surveyed recently,” said university expert Hoang Thi Hue.

“It is likely that if Vietnamese businesses continue using low technologies, the country will soon become a dump for the world’s backward technology,” Quan warned.

Many National Assembly members said that low technological improvements and low labour capacity had led to the fact that Vietnam’s labour capacity was equal to 43 per cent of the average labour capacity within the ASEAN.

According to the World Bank, Vietnamese businesses are finding it difficult to seek different types of skills, such as technical (nearly 60 per cent), computer or general IT (nearly 30 per cent), foreign languages (nearly 60 per cent), work ethics (nearly 90 per cent), interpersonal and communications (60 per cent), and managerial and leadership skills (nearly 90 per cent).

|

Ousmane Dione Country director for Vietnam, World Bank

In 1999, the US Department of Labor famously predicted that 65 per cent of primary school children would end up in jobs not yet invented. In 2017, this number jumped to 85 per cent, according to Dell Technologies. We are looking at an unknown job landscape in the future. In human capital terms, Vietnam is well-positioned. It has achieved good basic education outcomes, reflected through strong results in international assessments such as PISA and Young Lives, and the country has a dynamic young generation that can embrace and adapt to changes. Vietnam also ranks seventh in terms of improvements to universal health coverage. But the nation is aging. The share of Vietnam’s population in working age peaked in 2017, and is now on the decline. By 2050, it is expected that one out of every five Vietnamese will be over 65 years old. A critical challenge is that only 8 per cent of the labour force has university education, insufficient to make the leap into Industry 4.0. Workers need to be equipped with the right skills mix to ride this wave. In order to stay ahead and embrace shifts in innovation, promoting digital literacy is important. Partnering with the private sector and citizens to leverage participation, creativity, and innovation in public services will be useful for the public sector workforce to keep up with the digital pace. For example, China has been able to move forward with transformative digital health services that can improve access and quality. This is empowered by plentiful domestic venture capital resources of $5-10 billion, promising initial public offering valuations, and the power of the public sector to integrate innovation quickly into service delivery models. These digital health initiatives include a telemedicine system called the Robot, that aims to boost care at village clinic level in Anhui, and the WeDoctor platform providing online access to health professionals and bookings for face-to-face appointments. Investing in research and development will be critical for Vietnam to join the frontiers of Industry 4.0. The oft-used motto “Made in Vietnam” should be replaced with “Researched and Developed in Vietnam.” |

VIR

Ousmane Dione Country director for Vietnam, World Bank

In 1999, the US Department of Labor famously predicted that 65 per cent of primary school children would end up in jobs not yet invented. In 2017, this number jumped to 85 per cent, according to Dell Technologies. We are looking at an unknown job landscape in the future.

In human capital terms, Vietnam is well-positioned. It has achieved good basic education outcomes, reflected through strong results in international assessments such as PISA and Young Lives, and the country has a dynamic young generation that can embrace and adapt to changes. Vietnam also ranks seventh in terms of improvements to universal health coverage.

But the nation is aging. The share of Vietnam’s population in working age peaked in 2017, and is now on the decline. By 2050, it is expected that one out of every five Vietnamese will be over 65 years old.

A critical challenge is that only 8 per cent of the labour force has university education, insufficient to make the leap into Industry 4.0. Workers need to be equipped with the right skills mix to ride this wave.

In order to stay ahead and embrace shifts in innovation, promoting digital literacy is important. Partnering with the private sector and citizens to leverage participation, creativity, and innovation in public services will be useful for the public sector workforce to keep up with the digital pace.

For example, China has been able to move forward with transformative digital health services that can improve access and quality. This is empowered by plentiful domestic venture capital resources of $5-10 billion, promising initial public offering valuations, and the power of the public sector to integrate innovation quickly into service delivery models.

These digital health initiatives include a telemedicine system called the Robot, that aims to boost care at village clinic level in Anhui, and the WeDoctor platform providing online access to health professionals and bookings for face-to-face appointments.

Investing in research and development will be critical for Vietnam to join the frontiers of Industry 4.0.

The oft-used motto “Made in Vietnam” should be replaced with “Researched and Developed in Vietnam.”

Ousmane Dione Country director for Vietnam, World Bank

In 1999, the US Department of Labor famously predicted that 65 per cent of primary school children would end up in jobs not yet invented. In 2017, this number jumped to 85 per cent, according to Dell Technologies. We are looking at an unknown job landscape in the future.

In human capital terms, Vietnam is well-positioned. It has achieved good basic education outcomes, reflected through strong results in international assessments such as PISA and Young Lives, and the country has a dynamic young generation that can embrace and adapt to changes. Vietnam also ranks seventh in terms of improvements to universal health coverage.

But the nation is aging. The share of Vietnam’s population in working age peaked in 2017, and is now on the decline. By 2050, it is expected that one out of every five Vietnamese will be over 65 years old.

A critical challenge is that only 8 per cent of the labour force has university education, insufficient to make the leap into Industry 4.0. Workers need to be equipped with the right skills mix to ride this wave.

In order to stay ahead and embrace shifts in innovation, promoting digital literacy is important. Partnering with the private sector and citizens to leverage participation, creativity, and innovation in public services will be useful for the public sector workforce to keep up with the digital pace.

For example, China has been able to move forward with transformative digital health services that can improve access and quality. This is empowered by plentiful domestic venture capital resources of $5-10 billion, promising initial public offering valuations, and the power of the public sector to integrate innovation quickly into service delivery models.

These digital health initiatives include a telemedicine system called the Robot, that aims to boost care at village clinic level in Anhui, and the WeDoctor platform providing online access to health professionals and bookings for face-to-face appointments.

Investing in research and development will be critical for Vietnam to join the frontiers of Industry 4.0.

The oft-used motto “Made in Vietnam” should be replaced with “Researched and Developed in Vietnam.”