A profession kept in the shadows

“This job is often looked down on,” he admitted. “So I’ve kept it from my family.”

For four years, he hid his work from even his wife and children.

When his eldest son, a university student in Hanoi, once asked what he did for a living, Mr. S. replied:

“Don’t worry about it. Just know I’m not doing anything wrong.”

Currently, Mr. S. is caring for a patient in Bach Mai Ward, Hanoi.

Each client stays with him from one week to two months, depending on their condition.

Sometimes he works in hospitals; other times, he visits patients’ homes.

However, he has a personal rule: never stay with one case too long.

“After every assignment, I need time to rest and heal myself,” he explained. “Sometimes the hardest part isn’t the physical labor - it’s the emotional pressure.”

His daily tasks include giving medicine, feeding, hygiene, mobility assistance, and massage therapy to ease chronic pain.

Though most of his patients are men, he once cared for an elderly woman and didn’t hesitate at all.

Heartbreak and healing

Throughout four years of caregiving, Mr. S. has encountered both gratitude and emotional pain.

He recalled one elderly male patient in intensive care, suffering from chronic heart disease.

For ten nights in a row, Mr. S. barely slept, staying by the bedside, rubbing the man’s back or massaging him whenever he groaned in pain.

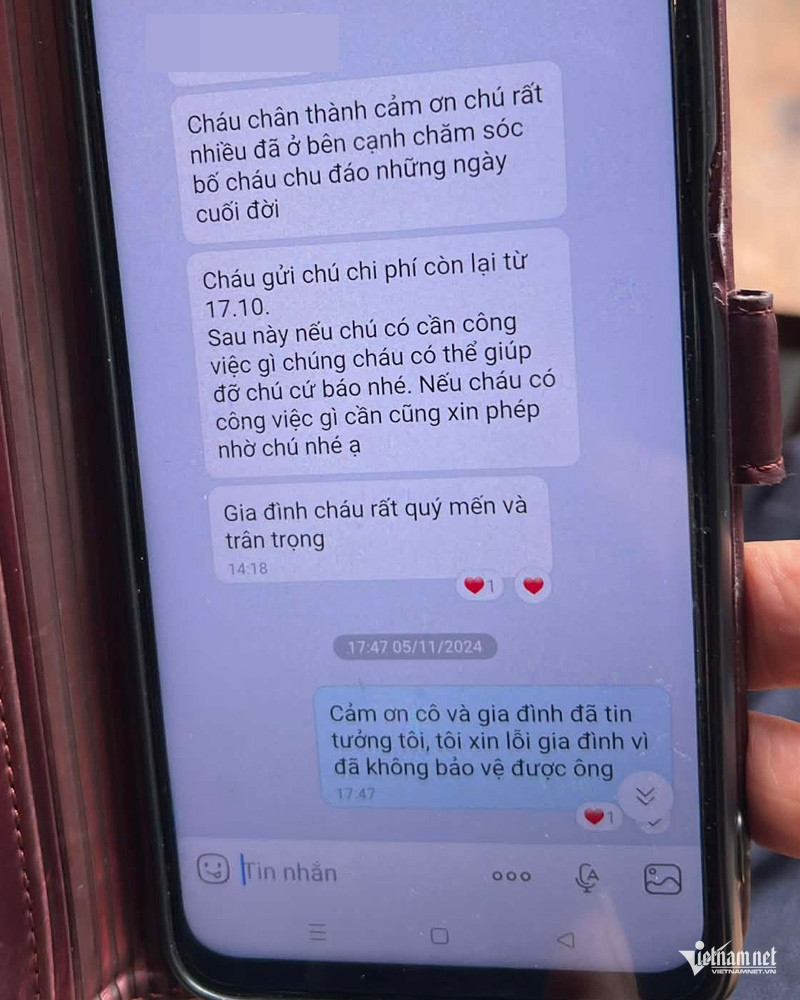

“I looked after him both in the hospital and later at home. His daughters were always grateful.

Even after he passed, they still call me now and then, telling me I’m welcome to ask for help anytime. That touches me deeply.”

There were tough cases too.

Once, he took care of a 75kg diabetic man confined to bed.

Initially, Mr. S. wanted to decline - he wasn’t sure he could physically handle the task. But the patient’s situation moved him.

“It was just an elderly couple, relying on each other. The wife was frail and had to crawl up the stairs to bring meals. I couldn’t walk away,” he said.

Though house chores were typically left to the family, Mr. S. took on everything, knowing the wife was too weak.

He had to clean, wash, and change the patient multiple times a day.

While most people massage 2–3 times daily, he performed acupressure up to ten times per day.

After that exhausting case, he returned home to rest and recover for a while.

The biggest challenge: human dignity

For Mr. S., the greatest pressure is not the physical demands, but the attitude of patients.

“When caring for the sick, patience must come first,” he said.

He understands that illness can make people irritable and difficult.

But occasionally, he’s faced blatant disrespect.

He recalled caring for a wealthy man - polite at first, but arrogant once his health improved.

“His words became condescending. He saw me as a servant.”

Mr. S. calmly addressed it, offering honest feedback - and the man changed his behavior afterward.

Despite the hardship, Mr. S. earns a modest but stable income, typically under $32 per day, depending on the case.

He’s satisfied with that.

For four years, he has rarely been without work - most of it coming from referrals or social media caregiver groups.

To Mr. S., dedication isn’t just part of the job - it’s his way of life.

“Only when you care for someone with skill, responsibility, and empathy - as if they were your own family - can you truly do this job well,” he said.

Thanh Minh – Nguyen Hanh