Every Tet (Lunar New Year) season, the national costume of Vietnam - the ao dai - returns to the spotlight, not only as a fashion choice but as a cultural symbol. This year, however, discussions go far beyond debates about modesty or elegance. A wave of mass-produced, foreign-inspired designs featuring Chinese-style frog buttons and qipao-like silhouettes has sparked concern about the slow erosion of Vietnam’s cultural identity.

The quiet invader in your shopping cart

A quick stroll through Tet markets or e-commerce platforms reveals a flood of so-called “modern ao dai” priced as low as $4–$8. But beneath the affordability lies a deeper issue. These garments often bear features like diagonal collars, central frog-button closures, and synthetic brocade fabrics associated with Chinese manufacturing.

For many retailers, these design elements are not deliberate cultural choices but economic decisions. Chinese textile factories offer ultra-low-cost production, and Vietnamese vendors under pricing pressure are left with few alternatives. Rather than investing in artisanal craftsmanship and traditional tailoring techniques, many opt for off-the-shelf patterns and foreign details that are easier - and cheaper - to replicate.

The result? When young Vietnamese post Tet photos wearing these garments, even local viewers might struggle to recognize the attire as distinctly Vietnamese - let alone foreign audiences. This is soft cultural erasure, not through war or politics, but through convenience.

Lessons from East Asia’s cultural battleground

The danger of diluted cultural symbols isn’t theoretical - it’s been fiercely contested in East Asia. At the 2022 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony, the sight of a performer in hanbok - claimed by China to represent its ethnic Korean minority - triggered uproar in South Korea. The Korean public saw it as a blatant cultural appropriation.

In response, Korea did more than protest. Through initiatives like the Hanbok Promotion Center, it modernized the hanbok, funding designers to adapt traditional attire for everyday and global use. Pop icons like BTS and BlackPink helped normalize hanbok in the modern wardrobe, turning it into a fashionable, recognizable emblem of Korean identity. Today, the jeogori (jacket) and chima (skirt) are as synonymous with K-culture as kimchi or K-pop.

Meanwhile, Japan took a different path -economically re-embedding kimono into daily life. Facing a 90% industry decline since its 1981 peak, Japan launched the “Kimono Passport” in Kyoto. Tourists wearing kimono receive discounts at museums and cafes, making the attire a living part of the city’s ecosystem, while sustaining local artisans.

Where to draw the line between innovation and distortion?

Vietnam’s own history is rich with ao dai innovation. The raglan-sleeved ao dai of the 1960s and the Lemur-inspired versions of the 1930s were modern for their time. But their strength lay in enhancing the form and function of ao dai - improving fit, comfort, and feminine elegance - while preserving its symbolic essence: the split flaps, upright collar, and silhouette.

In contrast, the recent influx of designs with large Chinese frog buttons and cheongsam cuts solves no functional problem. It doesn’t reflect a cultural exchange - it reflects economic laziness and design shortcuts. These foreign details, when they dominate, turn ao dai into a theatrical costume rather than a piece of heritage.

In today’s globalized fashion landscape, this isn’t just a question of style. It’s a question of intellectual property and cultural sovereignty. Mexico fought back when Zara appropriated Mixe tribal embroidery. Romania forced Louis Vuitton to remove and apologize for a blouse copied from Sibiu folk designs. In a flat world, uniqueness is power - and culture is capital.

Toward a flexible preservation strategy for ao dai

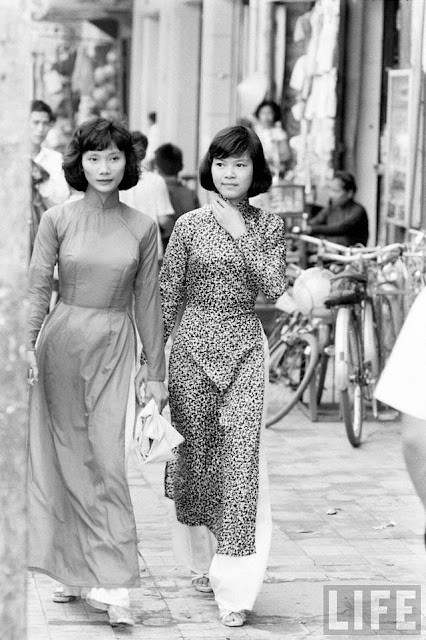

Vietnamese women in the past wearing Raglan-style ao dai. Photo: Life.

Vietnam cannot afford to simply lament each cultural misstep. What’s needed is a “flexible preservation strategy” that integrates identity, economy, and education.

First, the Ministry of Culture should collaborate with scholars and designers to establish voluntary recognition standards for “authentic Vietnamese ao dai.” This could follow India’s successful “Handloom Mark” model, offering consumers a clear way to identify heritage-respecting products.

Second, rather than enforcing ao dai as a mandatory school uniform, cultural education should be integrated into curricula. Students should learn why the ao dai is designed as it is -why the side flaps matter, why the collar stands tall -so pride replaces obligation.

Third, let culture feed on commerce. Imagine a “Ao dai Passport” in Hue, Hoi An, or Hanoi Citadel: tourists wearing verified traditional ao dai get free entry or discounts. This would create market demand for high-quality designs and reduce reliance on fast-fashion knockoffs.

Fourth, heritage advocates must shift from outrage to outreach -arming the public with knowledge rather than condemnation. Celebrities and filmmakers, whose fashion choices shape public perception, should treat each ao dai worn on screen or stage as a cultural statement, not a costume.

South Korea turned hanbok into a global fashion icon. Japan transformed kimono into a tourism asset. With its rich history and visual poetry, Vietnam can do the same for ao dai -if it chooses to innovate with care, not imitate without thought.

Let ao dai breathe with modern life -but make sure it breathes as Vietnam. Not as a blurred shadow of someone else’s past.

Nguyen Phuoc Thang (Hoa Binh University)