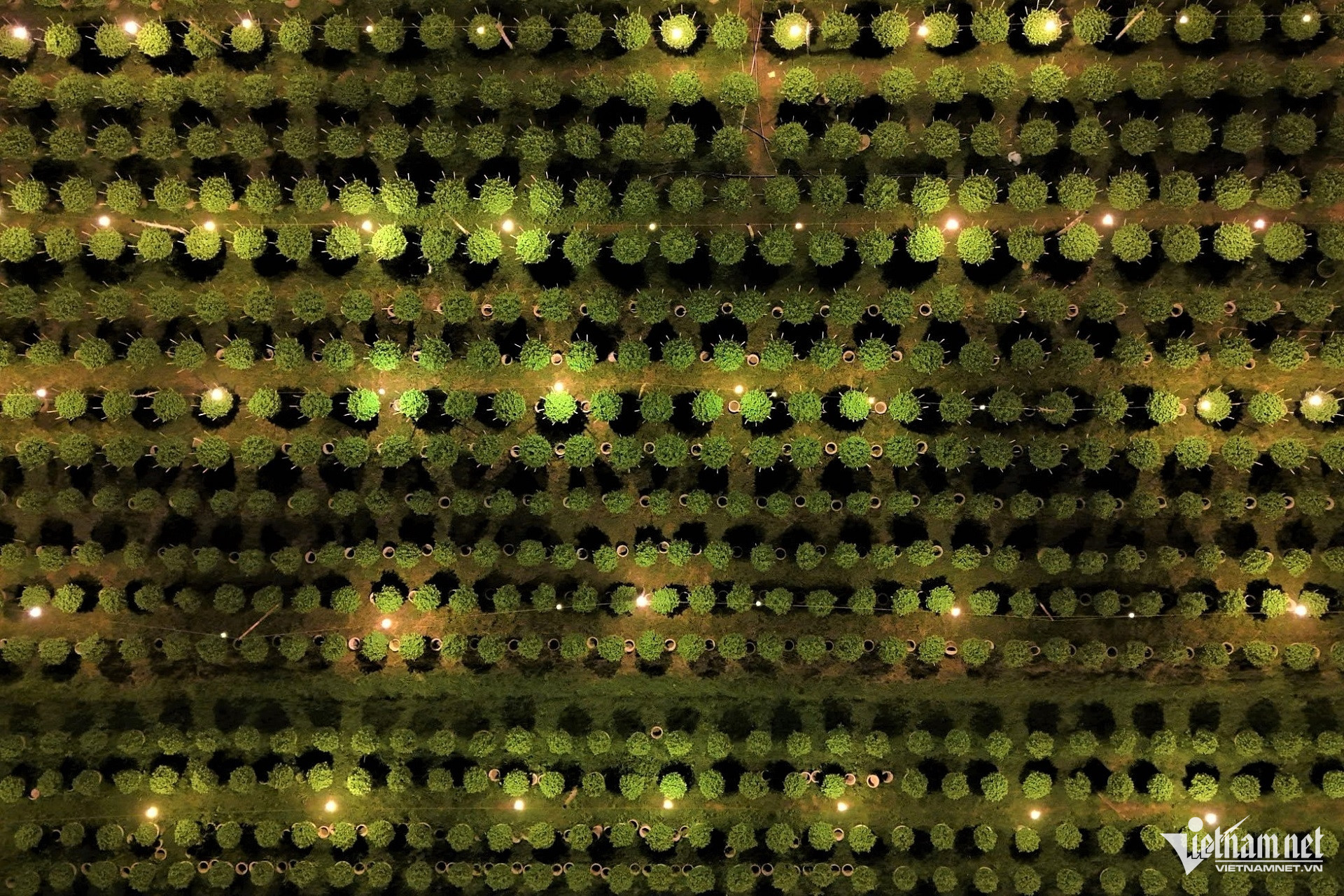

With just over a month to go until the Year of the Horse begins, the traditional flower village in Ve Giang Commune, Quang Ngai, bursts into light each night. From above, the scene is magical - an expanse of luminous gardens stretching across the floodplains of the Ve River, peaceful yet full of purpose.

This is the most critical phase of the chrysanthemum-growing season. Using electric lights to manipulate growth cycles, farmers control blooming time to align with Tet (Lunar New Year) demand.

For the people of Nghia Hiep, these lights do more than break winter’s chill. They maintain the rhythm of an entire season - one that determines livelihood, income, and the quality of New Year celebrations for hundreds of households.

Nghia Hiep is Central Vietnam’s largest chrysanthemum cultivation zone, with over 30 hectares under flower. More than 500 households grow Tet flowers here, supplying hundreds of thousands of pots to local and regional markets each year.

Growers explain that chrysanthemums are highly sensitive to light and temperature. In cold weather, with short days and long nights, the plants tend to bud too early, stunting leaf and stem development. Artificial lighting helps override these natural cues, prompting the plants to grow fuller and stronger before initiating the blooming phase.

Lights are typically switched on from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m. the next day. This artificial daylength is maintained for two to three months, depending on weather and chrysanthemum variety. Once plants reach 70–80cm in height, growers cut the lights - allowing the plants to transition into flowering mode just in time for Tet.

In the crisp air of late winter, the village shines all night. Under the warm yellow glow, rows of young, green chrysanthemums take shape - a quiet sign that the race toward the Lunar New Year is entering its final sprint.

Caring for each pot, counting down to bloom

At the garden of 54-year-old Tran Thi Luyen, thousands of small fluorescent bulbs cast even light over rows of tender chrysanthemums. This Tet, her family has planted nearly 1,500 pots - alongside asters and yellow buttons.

“Lighting is essential. Without it, prolonged cold will delay blooming, and we’d lose the whole season,” Luyen shared. “Just a few more days, and we’ll switch the lights off so the plants can begin budding.”

Not far away, Nguyen Van Minh’s family is growing around 1,000 pots. Already, 70% of his flowers have been pre-ordered by traders.

“For us, Tet flowers are both food and fortune,” he said. “In good years, each season brings in 150–200 million VND.” (Approx. 6,000–8,000 USD)

Yet production costs continue to rise - from electricity to fertilizer and labor. A few days of miscalculated care could mean uneven growth or premature budding, wiping out months of effort. Every pot must be monitored closely - from light to water to nutrients - to ensure a healthy, timely bloom.

The profession has deep roots in the village. Chrysanthemum farming in Nghia Hiep began roughly 50 years ago, when a few households brought seeds from Da Lat to trial. The experiment proved fruitful, and other families followed suit, forming the flower-growing hub seen today.

In January 2023, the "Nghia Hiep Flowers" brand was officially recognized by the Intellectual Property Office of Vietnam - marking a milestone in the village’s journey and setting a new path for this traditional craft.

Through cold nights and glowing lights, every pot of chrysanthemum carries the hope of a prosperous New Year - a flower for the market, and a symbol of renewal for the home.

Chrysanthemums in Nghia Hiep are nurtured night and day - each pot a family’s bet on a fruitful Tet season.

Ha Nam